It's not just whales

that need saving. Certain cheeses are on the brink of extinction and

risk being lost forever if we aren't careful. That was the premise of

Neal's Yard's Endangered Cheese Traditions event last month, which

was billed as a cheese tasting, but was also a lesson in how

cultural, economic and social changes are threatening to wipe out

some traditional cheeses. There was even a discussion about

transhumant lifestyles.

Don't worry, I had no

idea what a transhumant lifestyle was either until our host Andrew

Nielsen explained it to us (more on that later). Nielsen is a great

bear of an Australian, who gave up a career in advertising several

years ago to become a student of the 'fermentative arts'.

He first became a

cheesemonger at Neal's Yard, before moving to Burgundy to set up his

own vineyard called

Le Grappin. He's also an amateur brewer and

dabbler in cider. “Anything a little bit funky,” is how he put

it.

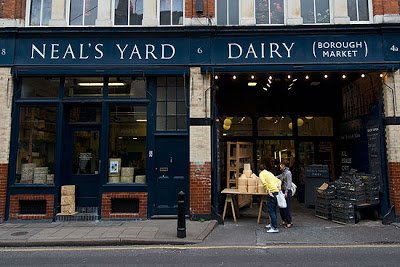

Nielsen picked a good

company at the start of his 'funky' odyssey. Neal's Yard Dairy is one

of Britain's great cheesemongers, specialising in British and Irish

cheeses and working closely with small farmhouse producers. Set up by

Randolph Hodgson in 1979, the company has two shops, one in Covent

Garden and one in Borough Market.

The Borough shop is

housed in a lovely high-ceilinged, glazed-brick building on the edge of

the market, which long ago was a stables for horses bringing Kentish

hops to the huge breweries that used to line the Thames. The tasting was held upstairs in what would have been the hay

loft.

The cheeses (starting

at 12 o'clock on the plate) were:

Cotherstone - a

pasteurised cows' milk cheese made by Joan Cross in County Durham

Sparkenhoe Red

Leicester - an unpasteurised cow's milk made by David and Jo Clarke

near Upton in Leicestershire

Abbaye de Tamie -

made in the Haute Savoie, France, with unpasteurised cows' milk and

matured by Herve Mons.

Beaufort d'Alpage -

an unpasteurised cow's milk made by Robert Peret in the Haut Savoie

Salers du Burons - an

unpasteurised cows' milk cheese made by Marcel Paille in the

Auvergne, France

Pecorino di Fossa -

an unpasteurised ewes' milk cheese made by Walter Facchini in Umbria

Bleu de Termignon -

made by Catherine Richard in the Haut Savoie from unpasteurised cows'

milk

Stichelton - Made by

Joe Schneider at the Welbeck Estate in Nottinghamshire to a Stilton

recipe, but using unpasteurised milk (so it's not allowed to be

called Stilton.

The lethal drinks

combo, from left to right, was: Saison Dupont Belgian beer, Asturian

Llagar Herminio cider, Arenae Malvasia de Colares wine from Portugal,

and Kernel Brewery porter.

All the cheeses and the

drinks are on the brink of extinction with just a handful of

producers still making them. You might argue that there are loads of

companies making Red Leicester in the UK, but Nielsen's definition of

a 'real' cheese is one made in a traditional farmhouse way (eg, by

small producers with their own herd using raw milk). Taking that

definition, real Red Leicester actually became extinct during the

second world war when farms were forced to sell their milk to the

government and large-scale factory production took over. That was

until it was revived in 1995 when Sparkenhoe was set up.

Other cheeses are on

the edge because they are such hard work to make. The Salers du

Burons requires the cheesemaker to live high in the

mountain for months on end as the cows move further up the slopes. This is the transhumant

lifetsyle, I mentioned earlier, but people just don't want to live

that way any more. “If you're an 18 year old French boy, you want

to be going to discos, not living up a

mountain with a load of cows,” said Nielsen.

The cheese itself was

full-on with an earthy almost musky flavour. You could see why it has

waned in popularity as tastes have changed. As the chap next to me

said, “You have to wonder whether this one really is worth saving.”

The Pecorino de Fossa

is struggling for similar reasons. It had a lot of meaty flavours

going on and quite an acidic bite. The cheese has been made up in

the hills around Umbria for centuries where it is covered in herbs

and buried it in hay for several months. It's such back-breaking,

labour intensive work that there are only two producers left.

Some of this might

sound a bit worthy, but the evening was actually great fun mainly

because Nielsen was such a knowledgeable and entertaining speaker.

For most of the night he was a blur of energy, scribbling on flip

charts and holding up photos, only stopping to take a few sips of

beer. Like all true curd nerds, he got particularly excited explaining

the science of coagulation (look at the love in this

picture).

The next morning, I tried to work out

which cheeses I would personally fight to save. The world would be a

poorer place without Cotherstone, Sparkenhoe and

Stichelton. I also liked the Beaufort and Abbaye de Tamie (which is

very similar to Reblochon), but I could definitely live without the

Pecorino, Salers and Bleu de Termignon. They were just too 'funky'

for me. Sometimes cheeses go to the great monger in the sky for a

good reason.

Endangered Cheese

Traditions is one of many different

tastings run by Neal's Yard. They all last about two hours

and cost £50.

I'm not shy when it comes to asking for tasters in cheese shops. Nibbling on a few slices while shooting the cheese with a fellow curd nerd is half the point of going to a good independent. Any self respecting retailer should be more than happy to let you try before you buy.

I'm not shy when it comes to asking for tasters in cheese shops. Nibbling on a few slices while shooting the cheese with a fellow curd nerd is half the point of going to a good independent. Any self respecting retailer should be more than happy to let you try before you buy.