|

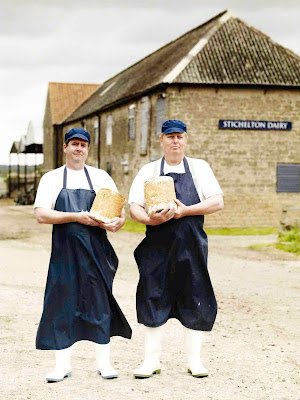

| L to R: Joe Schneider and Randolph Hodgson |

While most booze-fuelled brainwaves evaporate in the cold light of morning, this one continued to gnaw away at both Hodgson and Schneider to such an extent that in 2006 they opened a new dairy in conjunction with the Welbeck Estate in Nottinghamshire.

The only problem was that despite making blue cheese to a Stilton recipe in the heart of Stilton country, they weren't allowed to use the name. Under EU rules, Stilton must be made with pasteurised milk, so they were forced to call it something different. They ended up with the cheekily similar Stichelton - the earliest-recorded name of the village of Stilton.

It's a much-told story in cheese circles, but what's not so well known is that Stichelton has written to Defra to try to get Stilton's Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) amended to include unpasteurised milk. So far, Defra have yet to make a decision on the matter. “I could make Stilton with bananas, but a raw milk version isn't allowed. That's obviously perverse,” says Schneider. “The PDO should never exclude a cheese like ours. It's the only PDO in the whole of Europe that stipulates a cheese should be made with pasteurised milk. All the others stipulate the exact opposite.”

Stichelton consulted with the Specialist Cheesemakers' Association (SCA) when it was setting up and relations between the two groups remain cordial, if a little strained. The SCA included pasteurisation in the terms of the PDO in 1996 and the organisation has been known to send stiff letters to people if they refer to Stichelton as Stilton in print.

“I understand their point of view. They really don't want some yahoo farmhouse cheesemaker making a Stilton that's not safe and have an incident that might besmirch their brand, which they've worked really hard at building,” says Schneider. “But our argument is that the PDO isn't there for that reason. The PDO doesn't address issues of branding or hygiene. It's simply there to protect regional traditional foods.”

* To continue reading

this article, which was first published in the September issue of Fine

Food Digest, click here and turn to p27.

.jpg)