|

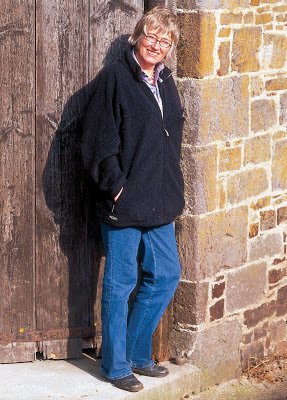

| Mary Quicke: a way with words |

There's no denying that Mary Quicke has a way with words. The transcript of my interview with the award-winning cheddar maker is punctuated with lovely turns of phrase as she goes into detail about the farm and her cheese.

Take this line about how eating good cheese focuses the mind on the here and now: “It's an education in being present. It's about the moment, which is where real happiness lies.”

Then there is a mention of Tess of the d'Urbervilles as she explains women's role in cheesemaking, followed by a story about Slow Food, where a French acquaintance described her cheese as having a 'palier' (grand staircase) of flavours.

The poetic language is not surprising when you discover that Quicke once studied for a PhD in English literature. That was while she was living in London, but her heart was always back on the family farm in Devon to where she returned in 1984, working alongside her parents Prue and Sir John Quicke and eventually taking over the business.

The Quicke family has farmed near the village of Newton St. Cyres for 450 years, but the dairy was only built in 1973. By this stage Quicke's father was deep into agri-politics (for which he was knighted), so it was her mother that was actually the driving force behind the business, while somehow managing to raise six children at the same time.

Today the 1,500 acre farm has a 500 strong herd of cows and produces around 300 tonnes of cheese each year, the vast majority of which is cloth-bound cheddar, both pasteurised and unpasteurised.

The fact that Quickes has been run by women for over 30 years has had a major impact on the cheese itself, says Quicke, who was awarded an MBE in 2005. “There is something distinctive about cheddar made by female cheese makers. It's said that women's palates are more sensitive. Of course some men's palates are wonderfully sensitive, but there can be a boy thing of wanting flavour that hits you between the eyes. As a business we've always prized complexity, subtlety, balance and length of flavour. Is that because it's a female thing? We want to be seduced and allured on our way to pleasure; not beaten up!”

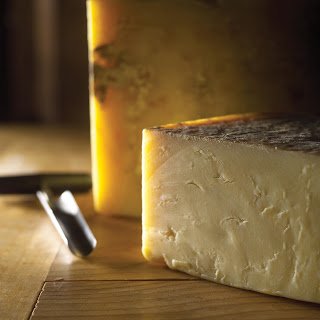

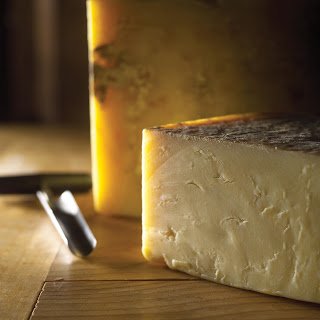

A mature Quickes cheddar has a creamy front, followed by some acidity, rich savoury flavours and caramel notes at the finish, she says. Achieving these layers of flavour depends on several factors. On the farm, Quickes rears cross-bred cows (Kiwi Friesian, Swedish Red and Montbeliarde) to get the required balance between fats and proteins in the milk. The cattle also graze on green Devon grass for around 10 months of the year, much longer than most dairy cows, which means the milk is rich in nutrients and complex flavours pretty much all year round.

The cheese-making process is also obviously key to achieving complexity. Quickes cooks (scalds) the curds at a slightly higher temperature than most to achieve a creamy flavour and, like other farmhouse cheesemakers, uses a complicated blend of different cultures. Known as 'starters', these are added to the milk at the beginning of the cheese making process. The cultures feed on lactose, creating lactic acid, which helps curdle the milk and flavour the resulting cheese.

Most industrial cheesemakers use simple single strain starters, which are far easier and more reliable to use but lack subtlety, says Quicke. “They have started using a type of single-strain starter called Helveticus, which is common in Swiss cheese. It typically gives very sweet flavours and covers up a multitude sins. The supermarkets have told their cheesemakers that they have to use it and so cheddar has started to become this sweet thing that is accessible and easy.”

Despite these concerns, Quickes does actually supply the supermarkets, including Waitrose, Tesco, Sainsbury's and Morrisons. Around 20% of sales are to the multiples, with independents making up 54% and exports 26% of the business.

It seems a risky strategy that could alienate independents, but Quicke is keen to explain her reasoning. “The supermarkets select a more forward flavour, which is less complex and balanced than the cheeses that go to the independents. It's good for us to be able to take them out of the way of the independents. The next step is to distinguish the different types. We need to label it up differently.”

Labelling will also have to change if Quickes ever becomes part of the EU's Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) scheme protecting West Country Farmhouse Cheddar. The company contributed its views when the PDO was set up in 1996, but eventually decided not to take part.

Quicke has recently enquired about joining, but her cheese is made in a slightly different way to the rules of the PDO. It means the regulations would have to be amended, something that is under discussion at the moment. There's no way Quicke would change her recipe to meet the PDO. That might compromise the 'grand staircase' of flavours she has worked so hard for in her cheddar.

www.quickes.co.uk

* A version of this was first published in the Cheeswire section of Fine Food Digest March 2012

From the dense woods around Alba that hide pungent white truffles to the neatly staked vineyards of Barolo, food and drink is written into the landscape of Piedmont. This hilly corner of North West Italy is home to picturesque hazelnut orchards and marshy fields of risotto rice, while Piedmontese cattle graze the fertile land on their way to producing sweet milk and meltingly soft beef. Wherever you go in Piedmont, you are never far from good food.

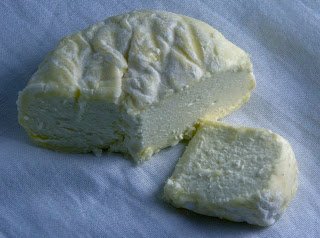

From the dense woods around Alba that hide pungent white truffles to the neatly staked vineyards of Barolo, food and drink is written into the landscape of Piedmont. This hilly corner of North West Italy is home to picturesque hazelnut orchards and marshy fields of risotto rice, while Piedmontese cattle graze the fertile land on their way to producing sweet milk and meltingly soft beef. Wherever you go in Piedmont, you are never far from good food.  In the Langhe - a wild and rugged area of the Cuneo province, high in the foothills of the Alps - the Cora family give full expression to the stunning countryside around their small dairy by wrapping goats' milk Robiola in leaves from the local woods.

In the Langhe - a wild and rugged area of the Cuneo province, high in the foothills of the Alps - the Cora family give full expression to the stunning countryside around their small dairy by wrapping goats' milk Robiola in leaves from the local woods.