The past few months have seen me working on a new project with fellow food and drink writers in Brighton. Together we've set up something called The Brighton Food Society, which is loosely based on the 'sociedades gastronmicas' or 'txokos' in the Basque Country.

In Spain, these are male-only societies that gather in club houses to cook for friends and family, celebrating the Basque region's fantastic ingredients. Ours is a little different int that we're open to men and women, and our core founding members are all food and drink writers, broadcasters and bloggers.

Our four-course launch meal, celebrating Sussex produce, was held earlier this month with a 35-strong guest list, including other food writers, chefs and food producers. There's more on the night

here.

As well as the dessert, the job of sorting the cheese course naturally fell into my lap. This is pretty ironic considering I used to be a bit sniffy about Sussex cheeses. Luckily, I recently did something of a

volte face on the whole subject and am now rather proud of the cheeses made in this part of the world.

Anyway, working with Hove-based cheesemonger

La Cave a Fromage, we came up with a pretty awesome selection of the best Sussex has to offer. We served 2.5kg of cheese for 35 people, which worked out at about

70g of cheese each. It doesn't sound a lot, but when you're eating good

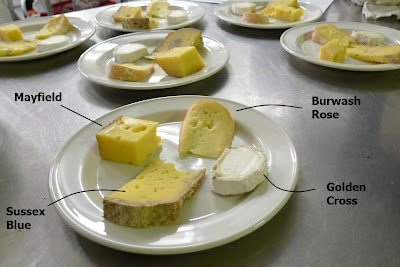

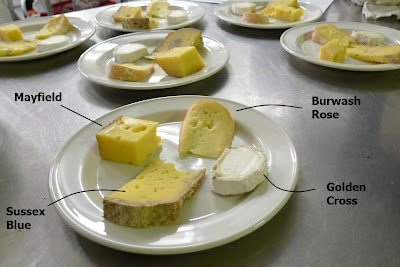

cheese with complex flavours, a little goes a long way. Here's what we went for:

Golden Cross

Golden Cross (Greenacres Farm, Whitchurch). An unpasteurised St Maure-style goat's cheese that is rolled in charcoal. Has a tart, lemony centre and a creamy layer just under the rind. One of Britain's great goat's cheeses.

Mayfield (Alsop & Walker, Mayfield). A pasteurised cow's milk cheeses that is part Gruyere, part Emmental with large holes. Quite a rubbery texture with sweet caramel and fruit notes, and a nutty finish.

Burwash Rose

Burwash Rose (The Traditional Cheese Dairy, Stonegate). A rich creamy pasteurised cow's milk cheese, which is washed in rose water to give it a perfumed, floral flavour.

Sussex Blue (Alsop & Walker, Mayfield). Sussex isn't blessed with a huge range of blue cheeses, but this one is a decent enough option. It's quite a mellow cheese with only very slight blueing, which gives a touch of spice, but nothing too powerful.

There are things I would do differently next time. A really hard cheese would have added more contrast in terms of texture and perhaps I should have included a sheep's milk cheese.

I should definitely have made more effort with the accompaniments. I served the cheese with apples, pears and some pretty basic crackers. That would have been a severe let down if it wasn't for some ace homemade plum chutney from fellow Society member

Sam Bilton and oat biscuits that were brought at the last minute by

Brighton's supper club queen Tina Horvath.

I'm already scheming for the next event, but what do you think are the crucial elements to the ultimate cheese board? And what local cheeses would you choose?