If you've got space for

dessert after working your way from nose to tail at St John in

Smithfield, the stand-out choice for cheese chaps and chapettes is

the Eccles cake and Lancashire.

Eating cheese with cake might sound a bit weird at first, but it makes sense when you think about it. The intensely sweet raisins in the Eccles cake act a bit like chutney to the crumbly

cheese, balancing out the curdy tang.

I've long liked a

slice of Stilton on my Christmas cake - a festive tradition that I

thought was practised throughout the country, but after asking around

nobody else seems to have heard of it.

Anyway, I decided to

dig a little deeper into the world of cheese and cake matching by

consulting the hive mind of Twitter. It turns out that I'm not

actually the only person out there who likes a bit of bakery and curd

action because my time line was soon flooded with suggestions.

Here we are getting

philosophical at Gail's Bakery in Soho.

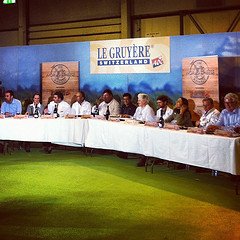

Here are the cheeses,

which included: Windrush Valley; Smoked Lincolnshire; Cropwell Bishop

Stilton; Kirkham's Lancashire; Appleby's Cheshire; Berkswell; Barkham

Blue; Tymsboro; St Wulfstan; Pecorino; Epoisses; Paxton's Cheddar;

Golden Cross.

And the cakes,

including: Chelsea bun; dark chocolate brownie; parkin; walnut cake;

Eccles cake; fruit cake; Wiltshire fruit loaf; plum bread; Madeira

cake; apple crumble cake; lemon drizzle.

We tasted around 15 different cakes and 15 different cheeses, trying combinations that had been recommended on Twitter or we thought would be interesting. In total we probably tried around 30 different matches. Here in ascending order are our top five... drumroll....

FIFTH PLACE

Epoisses and

Botham's plum bread

Plum bread is a

speciality of Lincolnshire and is traditionally eaten with a slice of

Lincolnshire Poacher. Fair enough, but we felt the plum bread acted

as a good neutral base for the spicy meaty flavours of Epoisses.

FOURTH

Pecorino and Gail's

lemon drizzle cake

The Pecorino was quite

austere with a hard almost crunchy texture and salty tang, which was

brilliant at cutting through the cake's sweetness. It also matched up

to the intense citrus flavour.

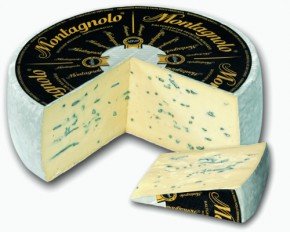

THIRD

Roquefort and Paxton's

fruit cake (pictured above)

We'd almost given up on

finding a cake that could match the might of Roquefort. Most

combinations were pretty disgusting, until we broke out the fruit

cake. The sweet candied fruit contrasted beautifully with the salty

sharpness of the cheese. Potent.

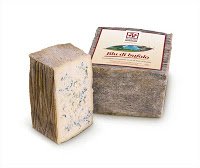

SECOND

St Wulfstan and Gail's

apple crumble cake (above)

One is a yoghurty

organic cow's milk cheese. The other is a moist, spicy apple cake

that crumbles at the slightest touch. Squish them together and you

have something that transcends the crude and simplistic categories of

'cake' and 'cheese'. It should have its own name, like 'chake' or 'cheeke'.

An almost spiritual experience.

FIRST PLACE & OVERALL WINNER

Tymsboro aged goat's

cheese and Gail's chocolate brownie (above)

Yes, you read that

right. Goat's cheese and chocolate brownie was the clear cake and cheese

champion. In the cake corner, with a steely glint in its eye, was an

insanely rich brownie made with three types of chocolate at 53%,

70% and 100% cocoa content. In the curd corner, wearing the white

trunks, was a 6-7 week aged pyramid of Tymsboro, with almond notes

and a proper goaty tang. You might think they would beat seven bells

out of each other, but the flavours

were actually perfectly attuned to each other. Rich, silky and

intense, it was a sexy Argentine tango rather than a punch up.

A few hints

and tips on cake and cheese matching

● You need a surprisingly

large slice of cheese to balance out the sweetness of the cake. A

50/50 ratio is about right, although perhaps a bit less cheese with

big boys like Epoisses and Roquefort.

● You're generally on to

a winner if the cake contains dried fruit and spice. Fruit cake,

Eccles, Plum Bread worked with most cheeses.

● Not all cakes are

created equal. Generally the cakes I bought in Waitrose and M&S

like the walnut and the parkin were a real let down compared to those

from Gail's, which were much fresher. Good cheese should not be

wasted on bad cake.

● I'll probably get some

stick from irate Mancunians over this, but Eccles cakes go better

with Stilton than Lancashire cheese. There I've said it.

● Finally, Chelsea buns

and Stilton should not mix. Ever.

With thanks to the

following Twitterers, whose suggestions were all definitely worth a

try (except for the smoked cheddar with brownies, which was just

wrong on many levels).

@ApplebysCheese

Applebys Cheshire and Staffordshire oatcakes; pecorino and panettone.

@MissCay Apple pie and

cheese. It's big in Wisconsin apparently: “Apple pie without cheese

is like a kiss without a squeeze.”

Ribblesdale also makes

its own unpasteurised Wensleydale, using milk from a local pedigree

herd, as well as a pasteurised version and a new product called

Yorkshire Bowlers - red waxed balls of Wensleydale that look like

cricket balls.

Ribblesdale also makes

its own unpasteurised Wensleydale, using milk from a local pedigree

herd, as well as a pasteurised version and a new product called

Yorkshire Bowlers - red waxed balls of Wensleydale that look like

cricket balls.

.jpg)