|

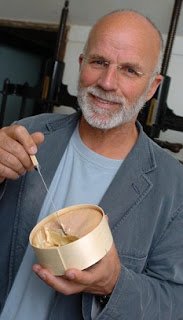

| The Cheese Chap discusses hair nets with Jamie Montgomery |

Montgomery’s cheddar is not short of admirers. Food writer Charles Campion describes it as a “world beater”, while Tom Parker-Bowles rates it as “the stuff of legend”. Then there’s the public, who eagerly snaffle the 500 truckles made each month at the family business’s 1,200-acre farm near Yeovil in Somerset.

The company’s success can be put down to owner Jamie Montgomery’s determination to remain faithful to the traditional cheesemaking practices of his grandfather, Sir John Langman, who took over the business in 1911. “My life is dedicated to making cheddar as my grandfather did, or at least as close as possible,” he says. “That might sound boring, but sticking to these principles can be incredibly challenging.”

Working with raw milk is a good example. Most cheesemakers pasteurise milk to eliminate any chance of disease - a ‘belt and braces’ approach to food safety that has more to do with the rise of supermarkets and huge dairies than making good cheese.

The problem with pasteurising is that it kills off ‘good’ bacteria that add complexity and depth of flavour.

|

| Montgomery's is made with milk from the farm's own herd |

Montgomery’s can vouch for the safety of its milk because it comes directly from the farm’s 170-strong herd of Friesians. Cheese is made daily to ensure the milk is absolutely fresh, but stringent health and safety laws still make life difficult - something that rarely affected Montgomery’s grandfather.

The biggest difficulty is the unreliable testing procedure for bovine TB - a disease that can spread through unpasteurised milk. “The tests are often inconclusive or throw up false positive results, which mean we have to slaughter,” explains Montgomery. “We test every six months and usually at least one cow has to be slaughtered. Yet in all the autopsies we’ve done, we’ve never actually found a case of TB.”

Beyond raw milk, Montgomery’s stands out from the cheddar crowd because it uses liquid starter cultures, which support a diverse range of bacteria and therefore create complex flavours in the final cheese. Most cheesemakers use freeze-dried cultures, which have a long shelf-life and are convenient to use. “But freeze drying is a heavy duty process and only some bacteria can take it,” says Montgomery. Cheese company Barber’s makes the starters using bacteria first collected from local farms in the 1950s.

Each batch of Montgomery’s cheddar produces around 18 of 23kg cheeses, depending on milk yields. A pint of starter is added to a churn of milk the day before processing to allow the bacteria to develop. This is then emptied into a vat of raw milk the next day and bacteria begin fermenting the sugar in the milk to make lactic acid. Calf’s rennet, which contains a catalyst enzyme, is then added to help coagulation.

Most cheddars use man-made vegetarian rennet to curdle the milk, but Montgomery argues that traditional calf’s rennet makes for a better end flavour. “I’ve tried the same cheese made with both and the difference in flavour is extraordinary.”

|

| The cheese is matured for atr least 11 months |

The curd is left to set before being cut to release the whey. The mixture is then mixed while warming to 41oC, a temperature that causes the bacteria to slow the creation of lactic acid. “Most will die off, but some will remain and keep adding flavour - it’s a fine balancing act,” says Montgomery.

The curds and whey are eventually channelled into a second vat, where much of the whey is drained off. The next stage in the process, known as cheddaring, is crucial to the final texture of the cheese and requires an expert touch. The cheesemakers run their hands through the rubbery chunks of curd to release more whey and slowly build up two sausage-shaped piles.

These are then cut into blocks, which are turned and stacked on top of each other repeatedly. This process helps drain off more of the whey, increases acidity and develops cheddar’s famous smooth texture. “We don’t want it to be amorphous like a block of soap; we want some fissuring,” says Montgomery.

The final slabs of curd are shredded in a peg mill and salted. “I think we’re one of only two producers in Britain still using a peg mill. Everyone else has chip mills, which slice the curds into smooth discs. But we like the brittle texture the peg mill produces.”

As output has slowly grown, Montgomery has been tempted to invest in a more efficient chip mill, but instead redesigned his old peg mill to run more quickly. “My grandfather would have appreciated that - he loved engineering and tinkering with machines.”

After milling, the curds are mechanically pressed in stainless steel moulds for three days. During this time the cheeses are also dipped in hot water to create a rind. The final stage of production sees the cheeses rubbed with lard and wrapped in muslin to prevent cracking and add support. They are then stacked in the maturing room where mould feeds on the lard and lets the cheese breathe.

The cheeses are matured for at least 11 months, with some aged for longer. Neal’s Yard takes a handful of two-year-old truckles each year. Interest in these strong, extra mature cheeses prompted a Times journalist to describe them as the ‘vindaloo’ of cheddar in a recent article.

“After the story appeared we had lots of enquiries from shallow people asking about our ‘cheddar with curry’, which was a nuisance,” says Montgomery. “The two year-old cheeses are almost a bit of fun. Generally, our cheese is at its peak a little earlier.”

For a man that takes his cheese seriously, the light-hearted media attention was obviously not appreciated by Montgomery. You can’t help but think his grandfather would have approved.

First published in the January issue of Artisan magazine

Made by HJ Errington of Lanark Blue and Dunsyre Blue fame, this Manchego-style ewes’ milk cheese is matured in cloth for six to 10 months and has a pretty mouldy rind. Sweet and earthy, Corra Linn is named after a waterfall in the Falls of Clyde. Selina Cairns, who has taken over production from her father Humphrey, also has some other new cheeses in the pipeline including one called Biggar Blue.

Made by HJ Errington of Lanark Blue and Dunsyre Blue fame, this Manchego-style ewes’ milk cheese is matured in cloth for six to 10 months and has a pretty mouldy rind. Sweet and earthy, Corra Linn is named after a waterfall in the Falls of Clyde. Selina Cairns, who has taken over production from her father Humphrey, also has some other new cheeses in the pipeline including one called Biggar Blue.